As a criminologist, I try to base my opinions on crime policy around “what works” with regard to findings from academic research. Certainly, there are times I have strong personal opinions about policies… but if the research says they don’t work (or work in a way that I wouldn’t expect), I need to abandon my opinions and stand behind the research.

With regard to gun violence, however, I find myself constantly frustrated by our lack of knowledge on “what works”. There are many opinions online about this, mostly by laypeople who have strong opinions. However, it’s important to note that the research is highly mixed.

The current state of our knowledge on gun violence can be found in the 2005 Report, “Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review“. This report collated dozens of studies and concluded that there is no strong evidence in favor or opposed to most policies.

Like I said… frustrating.

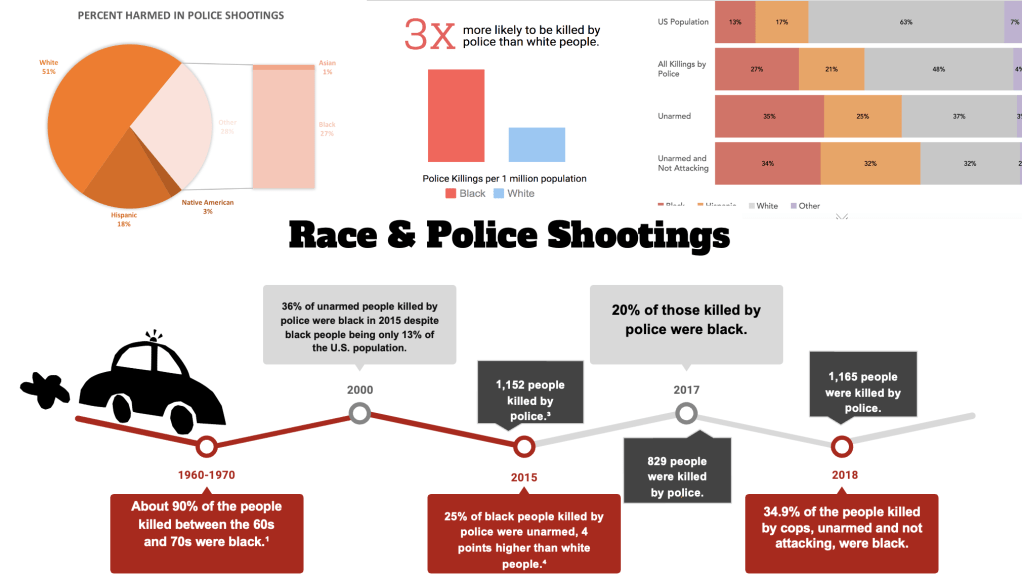

Friends of mine on both sides of the issue pass around data and charts on social media that support their positions, and to them the solutions seem very clear. So, it may be hard to understand why I’m saying that “we don’t know.” And that’s primarily because descriptive charts are only the first step in the data analysis process.

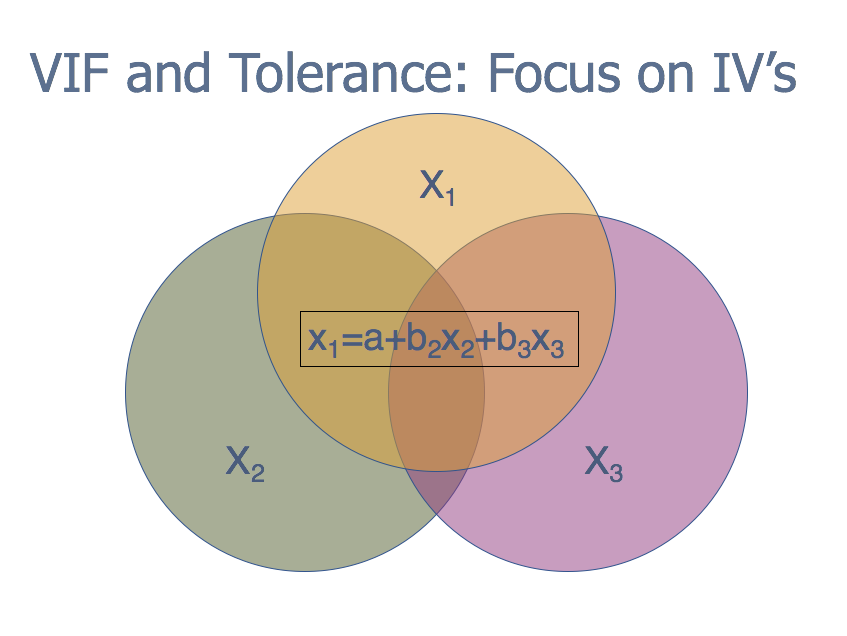

Researchers aiming to establish causality must:

- demonstrate an empirical correlation between the cause and effect

- confirm that the cause precedes the effect in time, and

- eliminate any other potential causes

I’l demonstrate this using a totally made up example (did you hear me, Internet? TOTALLY MADE UP! DO NOT FORWARD AS VALID!).

Let’s say that I live in a state that passed a more stringent background check requirement for gun ownership which took effect on 1/1/2003. I decide to see if this had an effect, so I collect the gun homicide rates in my state for each year between 1994 and 2015, and see what happened.

[NOTE: This is assuming the data I have found are valid and reliable, but that’s an issue for a different post.]

Anyway, I chart my data and it ends up looking like this:

This is pretty compelling information, right? Look at that big drop in gun homicides for 2003! The law must have had an effect!

But hold on…

We have only met Step #1 of the requirement for causality. We’ve demonstrated an empirical correlation–but this does not necessarily mean causation.

Let’s talk about Step #2: determining that the cause precedes the effect in time.

In this example, we might assume that it does, given that the law was effective January 1, 2003. But… how much time should it take the law to have an effect? If a lot of people own guns based on the lenient checks prior to 1/1/03, they still own those guns after the law goes into effect. It’s not like they would just “give them back” if the background check law changes. So, we shouldn’t see such a dramatic drop in one year. That seems fishy.

Changes in the law typically take time to have an effect–but how much? This is something we struggle with when trying to determine the causal ordering. In reality, a law like this might take years to have an effect, but do we really know how many? So maybe as the years tick by, the gun violence rate decreases and starts to tick down… that brings us to:

Step #3: How do we know it’s not really due to something else?

And this is the major sticking point for trying to find an answer. Governments change their laws all the time. New laws are constantly added, old laws are repealed, wording is changed, amendments are made, AND they usually try to reduce crime by trying several things at once. How could we know which of those things had an effect?

In a perfect world, we would enact a law and watch what happens to crime over several years with no other laws being enacted. But obviously, that’s not possible.

In addition, criminologists struggle to obtain quality data on this issue. In most cases, we haven’t collected it ourselves (i.e., we are dependent on data collected by police departments and other agencies), and there are other variables we’d like to have that aren’t included. Finding that information is very important for identifying those pesky “other potential causes”.

We have statistical methods that allow us to control for other potential causes, but sometimes too many things chance at once and those prove insufficient.

In sum, those simple charts being passed around on both sides only tell part of the story.

I really wish I knew what works here, but I don’t. Criminologists do know some things, however. Just to make you feel better, we can state with confidence that:

- The death penalty is not a deterrent

- DARE doesn’t reduce drug use in teens

- As immigration into the U.S. increases, the crime rate decreases (and also, immigrants commit fewer crimes than native-born Americans)

We know more things, but it’s nice to know a couple of things, at least.

P.S. Many people with strong opinions on these issues frequently engage in cherry-picking–only posting data/articles that support their position and ignoring any evidence contrary to their position. I strongly urge anyone interested in this issue to review all the information and share as much as possible without filters.